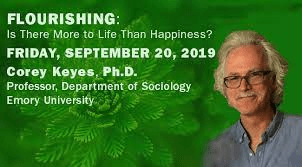

Emory University sociologist Corey Keyes on why we languish and how to flourish

Do you often feel like you’ve run out of gas? Lost your joie de vivre? Rudderless and unmotivated? You’re far from alone. There’s even a psychological term for what you’re experiencing. It’s called “languishing,” and Emory University sociologist Corey Keyes literally wrote the book on it. “Languishing is the neglected middle child of mental health, existing between depression and flourishing,” says Corey, author of the new book Languishing: How to Feel Alive Again in a World that Wears Us Down. “The pandemic brought it to the forefront, and now we have the opportunity to address a fundamental change that’s needed in the world.” ICONIQ’s Mikey Tom spoke with Corey about why we languish and how we can start flourishing.

ICONIQ: What is languishing and how widespread is it?

Keyes: Languishing is the absence of good mental health. I want to be very specific with the words because for so long clinical psychology and psychiatry have defined what mental health is. It was a black-and-white world where either you had a mental illness and needed help or you were free of mental illness and were fine. My work shows in a variety of ways that the following is true: the absence of mental illness doesn’t mean someone is mentally healthy.

In the book, I use the word “flourishing” as a stand-in for mental health to make it more understandable. In those cases, I’m talking about a way to diagnose the presence of good things going on in people’s lives. Languishing is the absence of a lot of those very important things. It’s the absence of things like purpose, a sense of belonging, and the idea that what you do on a daily basis matters or contributes worth or value to the world. You might not be able to make sense of what’s going on in the world, around you in society or in your community, or you might not be challenged to grow, to become a better person. People might try to describe it as feeling “blah” or “meh,” but that doesn’t do it justice. Languishing is the absence of some things that make life meaningful.

To put languishing in perspective, mental illness affects about 10% to 15% of the population in any given year. My research has shown that about 40% to 60% of some populations and groups of people suffer from languishing.

Is this a new phenomenon or has it persisted throughout history?

This has been part of the human condition but was forgotten for a very long time after the 12th century. Before the 12th century, believe it or not, there were eight deadly sins, not seven. The eighth sin was Acedia. Some people think it’s depression, but I disagree. It’s not the presence of sadness, it’s the absence of anything good. It’s feeling empty. It’s wondering, “Why am I doing this?” or “What is my purpose?” It’s the absence of a clear sense of why you’re going through all this toil. In the 12th, century it got folded into sloth and then it disappeared—nobody was paying attention to it.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health, which was adopted in the 1948 constitution, centers around the presence of well-being and not merely absence of disease and infirmity. Despite acknowledging it, health as the presence of something positive was never measured or studied because nobody took it seriously. Serious scholars, I was told, studied mental illness. The world has been fixated on the causes of death and illness and disease, not health.

Our friend Adam Grant wrote a New York Times column in 2021 that brought widespread attention to your work in the context of COVID-19, but you had been studying languishing for a very long time. Why is it now coming to the forefront and what are some of the other forces behind its rise?

The pandemic made a lot of people experience languishing for the first time in a powerful way. It took away all the things many took for granted, that made their life meaningful, and it took those things away without their permission. But this is a reality that billions of people had been living with well before the pandemic. Welcome to the world that most people with lower socioeconomic status live in all the time—having their dignity, their meaning, and their purpose, taken away from them, without their permission. Suddenly, we were all languishing for the first time I think and recognizing our common humanity in that regard.

Have you had personal experiences with languishing?

Some say my book is part memoir. I can’t separate my journey from languishing, having struggled with mental illness, depression, and PTSD, and having had to recover from a very traumatic first 11 years of my childhood. Those experiences moved me in this direction out of necessity. I was trying to find a better way and I had to find it on my own because there was very little support before my grandparents adopted me. I was on my own. And for the first time in my life, once I was transplanted into my grandparents’ home, I went from being in detention every day to being an honor student. My life changed. And I knew for the first time I understood that there was an alternative to the path that had been created for me, as well as the person that was taken from me through my trauma.

The book begins with me listening to King Biscuit Power Flower Hour, which is a radio show where I heard Jackson Browne for the first time, and his song Running on Empty. I was lying in my bed at 16 years old in my grandparents’ home, and I thought everything was good. But through the lyrics, I experience this emptiness, this numbness. And suddenly, I felt like somebody understood me. And then fast forward to today, there’s an artist named Em Beihold who wrote a song called Numb Little Bug, and it’s the modern equivalent of the song that spoke to me when I was a teenager. I knew languishing extremely intimately, and then it carved out a hole where depression came to live. I struggled with that all my life and I had to work through that pain and find a better way. That’s where flourishing comes from—from out of the ashes.

How is languishing different from depression?

People can get confused because sometimes those who are depressed will talk about things that are more like languishing. But you can be both depressed and languishing, and that’s a far worse place to be. I’ve shown that in my studies again and again. They do share one common symptom—a lack of interest in life—but the rest are diagnosed very differently. My diagnosis, which is 14 questions, is all about the presence and the absence of positive things like purpose, belonging, contribution, growth, and feeling happy or satisfied. Depression is when you’ve lost your interest in life, or you’re persistently sad, combined with four or more signs of malfunctioning. You can be depressed and, on top of that, have the complete absence of a purpose, contribution, and belonging.

The discussion has been around adults languishing, but what does this look like for kids?

One of the many studies I researched while writing this book focused on teenagers and their relationships with their parents. Spanning over 27 countries and 30,000 kids, this study asked respondents five questions: Are there people in their family who care about you? Is there someone in your family who will help you if you have a problem? Are there adults in your life that listen to you and take your views into account? Does your parent consult with you when they’re making decisions that affect your life? And finally, do you feel safe at home? Of the kids who said yes to all five of those things, over 80% were flourishing. Languishing increased as kids said “no” to more of the five questions, meaning that languishing probably comes from the absence of meaningful relationships with parents and adults.

The PBS Frontline documentary “The Lost Children of Rockdale County,” tells the story of how, between 1996 and 1999, a bunch of problems quickly emerged in this very wealthy Georgia county. There was this huge outbreak of syphilis, there was gun violence, and then a kid was killed in a parking lot when two boys were fighting, shocking the residents. The filmmakers uncovered the real problem: These wealthy, middle-class and upper-class families could provide all the material wants for these kids but nothing else—they had no time for their kids. These kids were adrift, lost, lonely, empty, trying to fill a void. They were languishing.

We think this is a problem that’s emerged very recently, but no, it’s been brewing. And it’s come to a head. Yes, social media is a problem. I think some kids use it as a surrogate because they don’t have the kind of connections that they need with adults in their lives. Those relationships are fundamental. And too many kids are saying, “I don’t have anyone in my life who cares about me, who listens to me, who helps me, who makes me feel safe and loved.”

You’re critical of the US healthcare system’s focus on treatment rather than prevention. What’s missing from how we’re managing the mental illness problem?

We keep hearing that mental illness is getting worse. And there’s an ongoing crisis, but nothing changes. We keep looking for our lost keys under the streetlamp because that’s the only place the light is shining, but we lost our keys somewhere else. We’ve lost sight of the fact we could be looking somewhere else. We will never treat our way out of the problem of mental illness. No public health challenges have ever been solved that way. I’m not arguing for an “either-or” world. I’m simply saying that if you want to deal with the crisis, you need to start preventing mental illness. And you can prevent a lot of this by promoting things like flourishing and addressing languishing before it becomes mental illness. Mental illness is just the tip of the iceberg. The Titanic wasn’t sunk by the tip of the iceberg, but rather by the huge mass that was underneath it, which in this case is languishing.

How can someone avoid falling into a languishing state?

There are five vitamins for addressing a flourishing deficiency that were informed by a longitudinal study where people were asked to evaluate how their previous day was. Did they feel joy? Did they feel pride? Did they feel contentment, and did they have a really good day or a bad day? What the researchers found was people who were flourishing, or moving towards it, did more of the five vitamins. They focused on: helping others or on learning something new; spirituality and religion (I call that transcendence); play as adults; and socialization—building connection and maintaining warm, trusting relationships, and a sense of belonging to the community.

I end my book using a favorite quote from Robert Kennedy to urge us all to start asking “why not” when it comes to having more people flourish and fewer people languishing: “Some [people] see things as they are, and say why. I dream of things that never were, and say why not.”